A very grainy image from the Times of Claes Oldenburg working on Hole on October 1, 1967.

The sculptor Tony Rosenthal, responsible for the much-loved spinning cube Alamo at Astor Place in New York, passed away on Tuesday. As is often the case with Times obituaries, there was a gem hiding inside: Alamo was supposed to remain at its current home for the month of October 1967, but neighborhood residents petitioned to keep the sculpture, and they got it.

Alamo had been installed as part of the Sculpture in Environment exhibition run by Samuel Adams Green and the New York City Office of Cultural Affairs, which placed twenty-five works around the city by well-known names like Alexander Calder, Barnett Newman, and David Smith (whose Zig IV, installed at Lincoln Center, is the only piece still in its original location) and some less-remembered names like Preston McClanahan and Richard Stankiewicz.

Seven years before Creative Time and a decade before the Public Art Fund, New York's city government was tackling some fairly radical art and organizing what Hilton Kramer declared was "probably the most extensive temporary display of new sculpture ever sponsored by a municipality." Olafur Eliasson's New York City Waterfalls, PLOT09, Chicago's Cow Parade, and every other public art event all owe some bit of their success to Sculpture in Environment.

Triangle with Ears, 1966. One of the two Calder sculptures shown in Harlem.

Each artist was allowed to pick their place in and contribution to the show. Alexander Calder picked Harlem, showing two sculptures outside the Lenox Terrace Apartments at 10 West 135th Street. "It's just that I feel sympathy for the Negro, and would like to make a gesture of friendship, if they would accept it," he told the Times, offering to donate his works to the Harlem community. (The artists included were almost uniformly white males, excepting Louise Nevelson, further complicating his wince-inducing - but certainly well-intentioned - remark.)

After being told by Green that he would not be allowed to create a traffic jam, declare New York a sculpture, create a free food machine, play a recurring, recorded scream, or craft a whimsical "silly subway" as his contribution to the show, Claes Oldenburg decided to dig a 6 x 6 x 3 foot ditch northwest of Cleopatra's Needle, just behind the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Aided by two gravediggers he paid $50 (working well before Chris Burden and Urs Fischer), Oldenburg excavated the ground and proceeded to refill it. Suzaan Boettger published a brilliant summary and analysis of the event in Artforum.

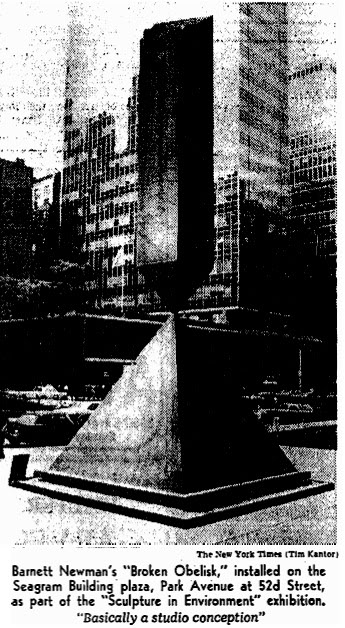

Broken Obelisk, 1963, in the Times. Hilton Kramer, generally displeased, provided the quotation.

Along with Calder, there were other more traditional sculptures. Barnett Newman's Broken Obelisk, 1963, for example, showed up outside the Seagram Building, just a few blocks from the Museum of Modern Art new atrium, which it would inaugurate in 2004. Hilton Kramer was harsh in his appraisal of the affair, noting that Green had been "thoroughly democratic in choosing good and bad sculptors alike." "Much of the work," he wrote, "violates rather than adorns the urban environment," establishing the line of critique on which shows of public art are largely judged up to this day.

No comments:

Post a Comment