Kathe Burkhart, Pillory of History, 1993

The first object one sees on entering White Columns is a large, golden instrument of torture, Kathe Burkhart’s Pillory of History (1993). Looking closer, around the holes carved for a prisoner’s head and hands are three finely inscribed words: “History repeats itself.” It’s a daring piece to put at the beginning of a retrospective tasked with crafting an historical account of the oftentimes remarkable, consistently unusual path the storied alternative space has taken over the last forty years.

While Gordon Matta-Clark is probably the artist most readily associated today with the early years of 112 Greene Street (the original name of White Columns), the show begins by highlighting the underlying philosophy espoused by cofounder Jeffrey Lew, who, in a 1978 interview posted on the walls of the gallery, admits, “None of the doors in 112 were ever locked,” a fact that succinctly embodies the freewheeling atmosphere of the space’s early years, in which artists randomly installed and removed works without any curatorial oversight. “There wasn’t a first show because everybody just arrived,” Lew explains. “I never understood the difference between selection and eliteism [sic].” That anarchic aesthetic, the show makes clear, did not last long.

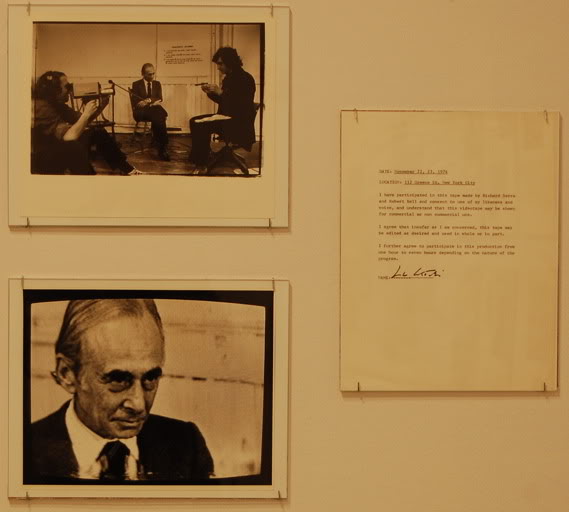

White Columns director Matthew Higgs and curator Amie Scally, after digging through the reportedly decrepit archives and combining their discoveries with material from artists’ holdings, selected a single exhibition for each year in the institution’s existence. Grouping this detritus with art from some of the shows, they have chronologically ordered the projects along the walls of the gallery in the form of a timeline, which abounds, especially in the first two decades, in surprises from a smaller, arguably more adventurous art world. Perhaps most remarkable is the 1974 entry, a contract signed by Leo Castelli agreeing to participate in Richard Serra’s game theory experiment and video Prisoner’s Dilemma, a sign of just how quickly and aggressively 112 Greene Street became a pivotal force in New York.

Richard Serra, Prisoner's Dilemma, 1974.

While Gordon Matta-Clark is probably the artist most readily associated today with the early years of 112 Greene Street (the original name of White Columns), the show begins by highlighting the underlying philosophy espoused by cofounder Jeffrey Lew, who, in a 1978 interview posted on the walls of the gallery, admits, “None of the doors in 112 were ever locked,” a fact that succinctly embodies the freewheeling atmosphere of the space’s early years, in which artists randomly installed and removed works without any curatorial oversight. “There wasn’t a first show because everybody just arrived,” Lew explains. “I never understood the difference between selection and eliteism [sic].” That anarchic aesthetic, the show makes clear, did not last long.

White Columns director Matthew Higgs and curator Amie Scally, after digging through the reportedly decrepit archives and combining their discoveries with material from artists’ holdings, selected a single exhibition for each year in the institution’s existence. Grouping this detritus with art from some of the shows, they have chronologically ordered the projects along the walls of the gallery in the form of a timeline, which abounds, especially in the first two decades, in surprises from a smaller, arguably more adventurous art world. Perhaps most remarkable is the 1974 entry, a contract signed by Leo Castelli agreeing to participate in Richard Serra’s game theory experiment and video Prisoner’s Dilemma, a sign of just how quickly and aggressively 112 Greene Street became a pivotal force in New York.

Richard Serra, Prisoner's Dilemma, 1974.

Other artifacts reveal a New York cultural world shifting throughout the 70’s and 80’s. A price list from 1988’s “Real World” offers Perfect Lovers, Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s twin clocks, for $350. (One set – of an edition of three – hangs over the front desk, ticking fifteen seconds apart on both days I visited.) Elsewhere, Allan McCollum submits a brief, typewritten proposal for a show in 1980. On the other side of the wall, remnants from Kim Gordon’s 1981 project, including a grainy photograph of the installation and a press release in which she quotes both Walter Benjamin and the Au Pairs, are on display. Her credibility is established through mention of her work with Glenn Branca and Rhys Chatham; Sonic Youth had yet to cut a record. It is these moments, when one witnesses artists on the verge of their breakthroughs, that are most pleasurable – and problematic.

There is, after all, a profound triumphalism inherent in the mode of selection on display. Far from Lew’s dream of an open utopia, the viewer bears witness largely to history’s winners and sees White Columns positioned as prophet. In the introductory text to the exhibition, though, Scally and Higgs are honest on this point, admitting that their undertaking is “celebratory” and “inevitably partial.” Hundreds of artists not in the exhibition also made use of the space and clout of White Columns, one is reminded. For an endless number of reasons their work didn’t last. Limiting their focus to a single work each year, the curators foreground this arbitrariness and, in their rigid chronological construction, reveal the contingency embedded in all art historical narratives. Entering the more contemporary end of the timeline and encountering works from less canonical names, this technique also allows for thrilling viewing: Where, one wonders, has White Columns bet correctly?

It is in inviting this glorification and questioning that “40 Years / 40 Projects” is at its best, outlining a thorough, persuasive advertisement for the importance of an active, engaged White Columns. The press releases, invitation cards, letters, and photographs come to function as non-sites, always pointing elsewhere: to installations disassembled (but present in the photographs of Matta-Clark projects), to political opportunities squandered (in the transcripts of Group Material discussions and the Silence = Death card on the entry bulletin board), and to art objects dispersed around the world. It is, for example, genuinely frustrating to squint at tiny photographs of Sarah Sze’s 1997 installation after reading Jerry Saltz describe it as a “Rimbaud-like vision of the abyss” in a page from Time Out New York torn out and tacked to the wall. Seeing the under-represented Jack Pierson’s rustic, elegant painting Lucky Strike (1986) provides only some temporary sense of relief.

There is, after all, a profound triumphalism inherent in the mode of selection on display. Far from Lew’s dream of an open utopia, the viewer bears witness largely to history’s winners and sees White Columns positioned as prophet. In the introductory text to the exhibition, though, Scally and Higgs are honest on this point, admitting that their undertaking is “celebratory” and “inevitably partial.” Hundreds of artists not in the exhibition also made use of the space and clout of White Columns, one is reminded. For an endless number of reasons their work didn’t last. Limiting their focus to a single work each year, the curators foreground this arbitrariness and, in their rigid chronological construction, reveal the contingency embedded in all art historical narratives. Entering the more contemporary end of the timeline and encountering works from less canonical names, this technique also allows for thrilling viewing: Where, one wonders, has White Columns bet correctly?

It is in inviting this glorification and questioning that “40 Years / 40 Projects” is at its best, outlining a thorough, persuasive advertisement for the importance of an active, engaged White Columns. The press releases, invitation cards, letters, and photographs come to function as non-sites, always pointing elsewhere: to installations disassembled (but present in the photographs of Matta-Clark projects), to political opportunities squandered (in the transcripts of Group Material discussions and the Silence = Death card on the entry bulletin board), and to art objects dispersed around the world. It is, for example, genuinely frustrating to squint at tiny photographs of Sarah Sze’s 1997 installation after reading Jerry Saltz describe it as a “Rimbaud-like vision of the abyss” in a page from Time Out New York torn out and tacked to the wall. Seeing the under-represented Jack Pierson’s rustic, elegant painting Lucky Strike (1986) provides only some temporary sense of relief.

Jack Pierson, Lucky Strike, 1986

Viewed from today’s frenetic, relatively prosperous art world, the early anarchic years of 112 Green Street at first appear tremendously liberating, but it’s also clear that there was very little at stake. By the mid-1980’s, in the midst of the AIDS crisis, continued urban decay, and the national dominance of conservative politics, White Columns would come to view itself as an essential space for the promulgation of oppositional political and aesthetic practice, a place where it was possible both for Judith Barry and Peter Halley to debate the efficacy of political art and for curators to stage a Sturtevant retrospective. A committed, discursive community had blossomed, the show argues.

In contrast to this rigor, some of the inclusions in the 1990’s and 2000’s seem less urgent and less interesting, products perhaps of their relatively halcyon times. Jessica Craig-Martin’s photograph from 1999 is alluring but almost flippant in its implied critique. The group show “What I Did on My Summer Vacation,” which invited artists and curators to take a disposable camera and document their idyll days (representing 1996) is novel but borders on being self-congratulatory, celebrating the hermetic networks of artists and curators that have dominated so much recent art.

Ultimately, though, as these rich, diverse fragments, these non-sites, inevitably point to the work they once promoted and supported, they also point to inspiring pasts, signaling how high a level of quality is required for today’s institutionalized White Columns to compete with its legendary history. In a new period of political crisis, then, Scally and Higgs seem to be welcoming a challenge.

1 comment:

Very interesting. Next time in NYC, we visit. - Roshi

Post a Comment